7th April 1920 - 11th December 2012 Ravi Shanker

Ravi Shankar

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other people named Ravi Shankar, see Ravi Shankar (disambiguation).

| Ravi Shankar পণ্ডিত রবিশঙ্কর | |

|---|---|

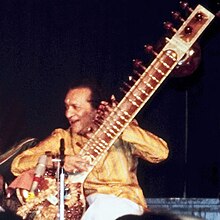

Shankar performing in 1988

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Robindro Shaunkor Chowdhury রবীন্দ্র শঙ্কর চৌধুরী |

| Born | 7 April 1920 Varanasi, United Provinces, India |

| Died | 11 December 2012 (aged 92) San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Genres | Hindustani classical music |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer |

| Instruments | sitar, vocals |

| Years active | 1939–2012 |

| Labels | East Meets West Music[1] |

| Associated acts | Uday Shankar, Allauddin Khan, Ali Akbar Khan,Lakshmi Shankar, Yehudi Menuhin, Chatur Lal, Alla Rakha, George Harrison,Anoushka Shankar, Norah Jones, John Coltrane |

| Website | RaviShankar.org |

Ravi Shankar (IPA: [ˈrɔbi ˈʃɔŋkɔr]; 7 April 1920 – 11 December 2012), his name often preceded by the title Pandit, was an Indian musician who was one of the best-known exponents of the sitar in the second half of the 20th century as well as a composer of Hindustani classical music.

Shankar was born in Varanasi (Kashi) and spent his youth touring Europe and India with the dance group of his brother Uday Shankar. He gave up dancing in 1938 to study sitar playing under court musician Allauddin Khan. After finishing his studies in 1944, Shankar worked as a composer, creating the music for the Apu Trilogy by Satyajit Ray, and was music director of All India Radio, New Delhi, from 1949 to 1956.

In 1956 he began to tour Europe and the Americas playing Indian classical music and increased its popularity there in the 1960s through teaching, performance, and his association with violinist Yehudi Menuhin andBeatles guitarist George Harrison. Shankar engaged Western music by writing compositions for sitar and orchestra, and toured the world in the 1970s and 1980s. From 1986 to 1992 he served as a nominated member of Rajya Sabha, the upper chamber of the Parliament of India. He continued to perform up until the end of his life. In 1999 Shankar was awarded India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna.

CONTENTS

[hide]EARLY LIFE[EDIT]

Shankar was born Robindro Shaunkor Chowdhury (Bengali: রবীন্দ্র শঙ্কর চৌধুরী)[2] on 7 April 1920 in Varanasi, to a Bengali family as the youngest of seven brothers.[2][3][4] His father, Shyam Shankar,was a Middle Templebarrister and scholar from East Bengal. A respected statesman, lawyer and politician, he served for several years as dewan (chief minister) of Jhalawar,Rajasthan and used the Sanskrit spelling of the family name and removed its last part.[2][5] Shyam was married to Shankar's mother Hemangini Devi who hailed from a small village named Nasrathpur in Mardah block of Ghazipur district, near Benares and her father was a prosperous landlord. Shyam later worked as a lawyer in London, England and [2] there he married a second time while Devi raised Shankar in Varanasi, and did not meet his son until he was eight years old.[2] Shankar shortened the Sanskrit version of his first name, Ravindra, to Ravi, for "sun".[2] Shankar had six siblings, only four of whom lived past infancy: Uday, Rajendra, Debendra and Bhupendra. Shankar attended the Bengalitola High School in Benares between 1927 and 1928.[citation needed]

At the age of ten, after spending his first decade in Varanasi, Shankar went to Paris with the dance group of his brother, choreographer Uday Shankar.[6][7] By the age of 13 he had become a member of the group, accompanied its members on tour and learned to dance and play various Indian instruments.[3][4] Uday's dance group toured Europe and the United States in the early to mid-1930s and Shankar learned French, discovered Western classical music, jazz, cinema and became acquainted with Western customs.[8]Shankar heard the lead musician for the Maihar court, Allauddin Khan, in December 1934 at a music conference in Kolkata and Uday convinced the Maharaja of Maihar in 1935 to allow Khan to become his group's soloist for a tour of Europe.[8] Shankar was sporadically trained by Khan on tour, and Khan offered Shankar training to become a serious musician under the condition that he abandon touring and come to Maihar.[8]

CAREER[EDIT]

Training and work in India[edit]

Shankar's parents had died by the time he returned from the European tour, and touring the West had become difficult due to political conflicts that would lead to World War II.[9] Shankar gave up his dancing career in 1938 to go to Maihar and study Indian classical music as Khan's pupil, living with his family in the traditional gurukul system.[6] Khan was a rigorous teacher and Shankar had training on sitar and surbahar, learned ragas and the musical styles dhrupad, dhamar, and khyal, and was taught the techniques of the instruments rudra veena, rubab, and sursingar.[6][10] He often studied with Khan's children Ali Akbar Khan and Annapurna Devi.[9] Shankar began to perform publicly on sitar in December 1939 and his debut performance was a jugalbandi (duet) with Ali Akbar Khan, who played the string instrument sarod.[11]

Shankar completed his training in 1944.[3] Following his training, he moved to Mumbai and joined the Indian People's Theatre Association, for whom he composed music for ballets in 1945 and 1946.[3][12] Shankar recomposed the music for the popular song "Sare Jahan Se Achcha" at the age of 25.[13][14] He began to record music for HMV India and worked as a music director for All India Radio (AIR), New Delhi, from February 1949 to January 1956.[3] Shankar founded the Indian National Orchestra at AIR and composed for it; in his compositions he combined Western and classical Indian instrumentation.[15] Beginning in the mid-1950s he composed the music for the Apu Trilogy by Satyajit Ray, which became internationally acclaimed.[4][16] He was music director for several Hindi movies including Godaan and Anuradha.[17]

1956–69: International career[edit]

V. K. Narayana Menon, director of AIR Delhi, introduced the Western violinist Yehudi Menuhin to Shankar during Menuhin's first visit to India in 1952.[18] Shankar had performed as part of a cultural delegation in the Soviet Union in 1954 and Menuhin invited Shankar in 1955 to perform in New York City for a demonstration of Indian classical music, sponsored by the Ford Foundation.[19][20] Shankar declined to attend due to problems in his marriage, but recommended Ali Akbar Khan to play instead.[20] Khan reluctantly accepted and performed with tabla (percussion) player Chatur Lal in the Museum of Modern Art, and he later became the first Indian classical musician to perform on American television and record a full raga performance, for Angel Records.[21]

Shankar heard about the positive response Khan received and resigned from AIR in 1956 to tour the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States.[22] He played for smaller audiences and educated them about Indian music, incorporating ragas from the South Indian Carnatic music in his performances, and recorded his first LP album Three Ragas in London, released in 1956.[22] In 1958, Shankar participated in the celebrations of the tenth anniversary of the United Nations and UNESCO music festival in Paris.[12] From 1961, he toured Europe, the United States, and Australia, and became the first Indian to compose music for non-Indian films.[12] Chatur Lal accompanied Shankar on tabla until 1962, when Alla Rakha assumed the role.[22] Shankar founded the Kinnara School of Music in Mumbai in 1962.[23]

Shankar befriended Richard Bock, founder of World Pacific Records, on his first American tour and recorded most of his albums in the 1950s and 1960s for Bock's label.[22] The Byrds recorded at the same studio and heard Shankar's music, which led them to incorporate some of its elements in theirs, introducing the genre to their friend George Harrison of the Beatles.[24] Harrison became interested in Indian classical music, bought a sitar and used it to record the song "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)".[25] This led to Indian music being used by other musicians and created the raga rock trend.[25]

Harrison met Shankar in London in June 1966 and visited India later that year for six weeks to study sitar under Shankar in Srinagar.[14][26][27] During the visit, a documentary film about Shankar named Raga was shot byHoward Worth, and released in 1971.[28] Shankar's association with Harrison greatly increased Shankar's popularity and Ken Hunt of AllMusic would state that Shankar had become "the most famous Indian musician on the planet" by 1966.[3][26] In 1967, he performed at the Monterey Pop Festival[29] and won a Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance for West Meets East, a collaboration with Yehudi Menuhin.[26][30] The same year, the Beatles won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year for Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which included "Within You Without You" by Harrison, a song that was influenced by Indian classical music.[27][30] Shankar opened a Western branch of the Kinnara School of Music in Los Angeles, in May 1967, and published an autobiography, My Music, My Life, in 1968.[12][23] In 1968, he scored for the movie Charly. He performed at theWoodstock Festival in August 1969, and found he disliked the venue.[26] In the 1970s Shankar distanced himself from the hippie movement.[31]

1970–2012: International career[edit]

In October 1970 Shankar became chair of the department of Indian music of the California Institute of the Arts after previously teaching at the City College of New York, the University of California, Los Angeles, and being guest lecturer at other colleges and universities, including the Ali Akbar College of Music.[12][32][33] In late 1970, the London Symphony Orchestra invited Shankar to compose a concerto with sitar. Concerto for Sitar and Orchestrawas performed with André Previn as conductor and Shankar playing the sitar.[4][34] Hans Neuhoff of Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart has criticised the usage of the orchestra in this concert as "amateurish".[35] George Harrison organised the charity Concert for Bangladesh in August 1971, in which Shankar participated.[26] After the musicians had tuned up on stage for over a minute, the crowd broke into applause, to which the amused Shankar responded: "If you like our tuning so much, I hope you will enjoy the playing more."[36] Although interest in Indian music had decreased in the early 1970s, the concert album became one of the best-selling recordings to feature the genre and won Shankar a second Grammy Award.[30][33]

During the 1970s, Shankar and Harrison worked together again, recording Shankar Family & Friends in 1973 and touring North America the following year to a mixed response after Shankar had toured Europe with the Harrison-sponsored Music Festival from India.[37] The demanding schedule weakened Shankar, and he suffered a heart attack in Chicago in November 1974, causing him to miss a portion of the tour.[38] In his absence, Shankar's sister-in-law, singer Lakshmi Shankar, conducted the touring orchestra.[38] The touring band visited the White House on invitation of John Gardner Ford, son of US President Gerald Ford.[38] Shankar toured and taught for the remainder of the 1970s and the 1980s and released his second concerto, Raga Mala, conducted by Zubin Mehta, in 1981.[39][40] Shankar was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Music Score for his work on the 1982 movie Gandhi, but lost to John Williams' ET[41]

He served as a member of the Rajya Sabha, the upper chamber of the Parliament of India, from 12 May 1986 to 11 May 1992, after being nominated by Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.[14][42] Shankar composed the dance drama Ghanashyam in 1989.[23] His liberal views on musical co-operation led him to contemporary composer Philip Glass, with whom he released an album, Passages, in 1990.[6]

Shankar underwent an angioplasty in 1992 due to heart problems, after which George Harrison participated in a number of Shankar's projects.[43] Because of the positive response to Shankar's 1996 career compilation In Celebration, Shankar wrote a second autobiography, Raga Mala, with Harrison as editor.[43] He performed in between 25 and 40 concerts every year during the late 1990s.[6] Shankar taught his daughter Anoushka Shankar to play sitar and in 1997 became a Regents' Professor at University of California, San Diego.[44][45] In the 2000s, he won a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album for Full Circle: Carnegie Hall 2000 and toured with Anoushka, who released a book about her father, Bapi: Love of My Life, in 2002.[30][46] Anoushka performed a composition by Shankar for the 2002 Harrison memorial Concert for George and Shankar wrote a third concerto for sitar and orchestra for Anoushka and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra.[47][48] In June 2008, Shankar played what was billed as his last European concert,[31] but his 2011 tour included dates in the United Kingdom.[49]

On 1 July 2010, at the Southbank Centre's Royal Festival Hall, London, England, Anoushka Shankar, on sitar, performed with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by David Murphy what was billed the first Symphony by Ravi Shankar. This performance was recorded and is available on CD. It is 40:52 minutes long and is composed of 4 movements (in the tempi allegro (fast), slow, scherzo (fast), finale (fast)) like a classical Western symphony but uses an Indian raga as the mode for each movement: I. Allegro (Kafi Zila) 9:21 minutes, II. Lento (Ahir Bhairav) 7:52 minutes, III. Scherzo (DoGa Kalyan) 8:49 minutes IV. Finale (Banjara) 14:50 minutes.[50] The website of the Ravi Shankar Foundation provides the information that "The symphony was written in Indian notation in 2010, and has been interpreted by his student and conductor, David Murphy."[51] The information available on the website does not explain this process of "interpretation" of Ravi Shankar's notation by David Murphy, nor how Ravi Shankar's Indian notation could accommodate Western orchestral writing.

STYLE AND CONTRIBUTIONS[EDIT]

Shankar developed a style distinct from that of his contemporaries and incorporated influences from rhythm practices of Carnatic music.[6] His performances begin with solo alap, jor, and jhala (introduction and performances with pulse and rapid pulse) influenced by the slow and serious dhrupad genre, followed by a section with tabla accompaniment featuring compositions associated with the prevalent khyal style.[6] Shankar often closed his performances with a piece inspired by the light-classical thumri genre.[6]

Shankar has been considered one of the top sitar players of the second half of the 20th century.[35] He popularised performing on the bass octave of the sitar for the alap section and became known for a distinctive playing style in the middle and high registers that used quick and short deviations of the playing string and his sound creation through stops and strikes on the main playing string.[6][35] Narayana Menon of The New Grove Dictionarynoted Shankar's liking for rhythmic novelties, among them the use of unconventional rhythmic cycles.[52] Hans Neuhoff of Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart has argued that Shankar's playing style was not widely adopted and that he was surpassed by other sitar players in the performance of melodic passages.[35] Shankar's interplay with Alla Rakha improved appreciation for tabla playing in Hindustani classical music.[35] Shankar promoted thejugalbandi duet concert style and claims to have introduced new ragas Tilak Shyam, Nat Bhairav and Bairagi.[6]

RECOGNITION[EDIT]

Indian governmental honours[edit]

- Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (1962)[53]

- Padma Bhushan (1967)

- Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship (1975).[54]

- Padma Vibhushan (1981)

- Kalidas Samman from the Government of Madhya Pradesh for 1987–88[55]

- Bharat Ratna (1999)[56]

Other governmental and academic honours[edit]

- Ramon Magsaysay Award (1992) and the .[57]

- Commander of the Legion of Honour of France (2000)[58]

- Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) by Elizabeth II for "services to music" (2001)[59]

- Honorary degrees from universities in India and the United States.[12]

- Honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Honorary Doctor of Laws from the University of Melbourne, Australia (2010)[60]

Arts awards[edit]

- 1964 fellowship from the John D. Rockefeller 3rd Fund

- Silver Bear Extraordinary Prize of the Jury at the 1957 Berlin International Film Festival (for composing the music for the movie Kabuliwala).[61]

- UNESCO International Music Council (1975)

- Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize (1991)[62]

- Praemium Imperiale for music from the Japan Art Association (1997)[6]

- Polar Music Prize (1998)[63]

- Three Grammy Awards

- Nominated for an Academy Award.[12][30][41]

- Recipient of the lifetime achievement Grammy (December 2012; posthumous)[64] like Glenn Gould, Charlie Haden, Lightnin' Hopkins, Carole King, Patti Page and the Temptations.

- Posthumous nomination in the 56th Annual Grammy Awards for his album "The Living Room Sessions Part 2".[65]

- First recipient of the Tagore Award in recognition of his outstanding contribution to cultural harmony and universal values (2013; posthumous)[66]

Other honours and tributes[edit]

- American jazz saxophonist [John Coltrane] named his son [Ravi Coltrane] after Shankar.[67]

PERSONAL LIFE AND FAMILY[EDIT]

Shankar married Allauddin Khan's daughter Annapurna Devi in 1941 and his son Shubhendra Shankar was born in 1942.[10] Shankar separated from Devi during the 1940s and had a relationship with Kamala Shastri, a dancer, beginning in the late 1940s.[68]

An affair with Sue Jones, a New York concert producer, led to the birth of Norah Jones in 1979.[68]

After Shankar separated from Kamalaa Shastri in 1981, Anoushka Shankar was born to Shankar and Sukanya Rajan. Shankar, however, lived with Sue Jones until 1986. He married Sukanya Rajan, whom he had known since the 1970s[68] in 1989 at Chilkur Templein Hyderabad, India.[69]

Shubhendra "Shubho" Shankar often accompanied his father on tours.[70] He could play the sitar and surbahar, but elected not to pursue a solo career. He died in 1992.[70] Norah Jones became a successful musician in the 2000s, winning eight Grammy Awards in 2003.[71] Anoushka Shankar was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best World Music Album in 2003.[71] Anoushka and her father were both nominated for Best World Music Album at the 2013 Grammy Awards for separate albums.[72]

Shankar was a Hindu and in his later years of life, a vegetarian.[73][74] He wore a large diamond ring which he said was "manifested" by Sathya Sai Baba.[75] He lived with Sukanya in Encinitas, California.[76]

Shankar performed his final concert, with daughter Anoushka, on 4 November 2012 at the Terrace Theater in Long Beach, California.

ILLNESS AND DEATH[EDIT]

On 6 December 2012, Shankar was admitted to Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, San Diego, California after complaining of breathing difficulties. He died on 11 December 2012 at around 16:30 PST after undergoing heart valve replacement surgery.[77]

The Swara Samrat festival organised on 5–6 January 2013 was dedicated to Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan where musicians like Shivkumar Sharma, Birju Maharaj, Hari Prasad Chaurasia, Zakir Hussain, Girija Devi etc. performed.[78]

DISCOGRAPHY[EDIT]

Main article: Ravi Shankar discography

BIBLIOGRAPHY[EDIT]

- Shankar, Ravi (1968). My Music, My Life. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-20113-1.

- Shankar, Ravi (1979). Learning Indian Music: A Systematic Approach. Onomatopoeia. OCLC 21376688.

- Shankar, Ravi (1997). Raga Mala: The Autobiography of Ravi Shankar. Genesis Publications. ISBN 0-904351-46-7.

Ravi Shankar - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

-

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ravi_Shankar

Ravi Shankar his name often preceded by the title Pandit, was an Indian musician who was one of the best-known exponents of the sitar in the second half of the ...

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ravi_ShankarRavi Shankar his name often preceded by the title Pandit, was an Indian musician who was one of the best-known exponents of the sitar in the second half of the ...

Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University

-

www.prsu.ac.in/

Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University Raipur CG. Prayer is not eloquence, but earnestness; not the definition of helplessness, but the feeling of it; not figures of

- www.prsu.ac.in/Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University Raipur CG. Prayer is not eloquence, but earnestness; not the definition of helplessness, but the feeling of it; not figures of

...

Pandit Ravi Shankar, Ustad Zakir Hussain and ... - YouTube

-

www.youtube.com/watch?v=fg_sHArZj4s

Jan 30, 2013 - Uploaded by Musicchiller-Entertainment 55

A part of the concert of 25th May 1993 at The Carnegie Hall. This is Raag Mishra Pilu and evening raga played ...

- www.youtube.com/watch?v=fg_sHArZj4sJan 30, 2013 - Uploaded by Musicchiller-Entertainment 55A part of the concert of 25th May 1993 at The Carnegie Hall. This is Raag Mishra Pilu and evening raga played ...

Pandit Ravi Shankar was unhappy as I was drawing more ...

-

timesofindia.indiatimes.com/.../Pandit-Ravi-Shankar.../41379379.cms

Sep 1, 2014 - Sitar exponent Ravi Shankar's wife Annapurna Devi says she had to choose between marital bliss over professional recognition — and she ...

- timesofindia.indiatimes.com/.../Pandit-Ravi-Shankar.../41379379.cmsSep 1, 2014 - Sitar exponent Ravi Shankar's wife Annapurna Devi says she had to choose between marital bliss over professional recognition — and she ...

Ravi Shankar - Home

-

www.ravishankar.org/

Oct 22, 2013 - COME and CELEBRATE the 95th BIRTHDAY OF Sitar Maestro Pt. Ravi Shankar Friday March 27, 7:00 pm. Guest of Honor Conductor David ...

- www.ravishankar.org/Oct 22, 2013 - COME and CELEBRATE the 95th BIRTHDAY OF Sitar Maestro Pt. Ravi Shankar Friday March 27, 7:00 pm. Guest of Honor Conductor David ...

Ravi Shankar Profile - Pandit Ravi Shankar Biography ...

-

www.iloveindia.com › Famous Indians › Musicians

Here is a brief profile and biography of Pandit Ravi Shankar. Read about information on Indian Sitar Player Ravi Shankar.

- www.iloveindia.com › Famous Indians › MusiciansHere is a brief profile and biography of Pandit Ravi Shankar. Read about information on Indian Sitar Player Ravi Shankar.

Pandit Ravi Shankar - Cultural India

-

www.culturalindia.net › Indian Music

Pandit Ravi Shankar is an internationally acclaimed sitar player. Know his life history in this biography of Pt. Ravi Shankar.

- www.culturalindia.net › Indian MusicPandit Ravi Shankar is an internationally acclaimed sitar player. Know his life history in this biography of Pt. Ravi Shankar.

Ravi Shankar - Biography - - Biography.com

-

www.biography.com/people/ravi-shankar-9480456

Ravi Shankar's sitar playing helped popularize classical Indian music in the United States. Learn more at Biography.com.

- www.biography.com/people/ravi-shankar-9480456Ravi Shankar's sitar playing helped popularize classical Indian music in the United States. Learn more at Biography.com.

Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University - Chhattisgarh

-

chhattisgarh.indiaresults.com › Chattisgarh

Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University is Chhattisgarh's largest and oldest institution of higher education, founded in 1964, and named after the first chief minister of ...

- chhattisgarh.indiaresults.com › ChattisgarhPt. Ravishankar Shukla University is Chhattisgarh's largest and oldest institution of higher education, founded in 1964, and named after the first chief minister of ...

RAIPUR UNIVERSITY RESULTS

-

OSWAL.SELFIP.COM/RAIPURRESULTS/

RAIPUR UNIVERSITY RESULTS, RAIPUR. EXAM NAME. ------SELECT EXAM NAME-------, B.A. 1 - SUPP, B.A. 2 - SUPP, B.A. 3 - SUPP, B.C.A- 1 SUPP, B.C.A.

- OSWAL.SELFIP.COM/RAIPURRESULTS/RAIPUR UNIVERSITY RESULTS, RAIPUR. EXAM NAME. ------SELECT EXAM NAME-------, B.A. 1 - SUPP, B.A. 2 - SUPP, B.A. 3 - SUPP, B.C.A- 1 SUPP, B.C.A.

...

Searches related to pt. ravi shanker

NOTES[EDIT]

- ^ "East Meets West MusicRavi Shankar Foundation". East Meets West Music, Inc. Ravi Shankar Foundation. 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Lavezzoli 2006, p. 48

- ^ a b c d e f Hunt, Ken. "Ravi Shankar – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d Massey 1996, p. 159

- ^ Ghosh 1983, p. 7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Slawek 2001, pp. 202–203

- ^ Ghosh 1983, p. 55

- ^ a b c Lavezzoli 2006, p. 50

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 51

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 52

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 53

- ^ a b c d e f g Ghosh 1983, p. 57

- ^ Sharma 2007, pp. 163–164

- ^ a b c Deb, Arunabha (26 February 2009). "Ravi Shankar: 10 interesting facts". Mint. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 56

- ^ Schickel, Richard (12 February 2005). "The Apu Trilogy (1955, 1956, 1959)". Time. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ "A lesser known side of Ravi Shankar". Hindustan Times. 12 December 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 47

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 57

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 58

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 58–59

- ^ a b c d Lavezzoli 2006, p. 61

- ^ a b c Brockhaus, p. 199

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 62

- ^ a b Schaffner 1980, p. 64

- ^ a b c d e Glass, Philip (9 December 2001). "George Harrison, World-Music Catalyst And Great-Souled Man; Open to the Influence of Unfamiliar Cultures". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ a b Kozinn, Allan (1 December 2001). "George Harrison, 'Quiet Beatle' And Lead Guitarist, Dies at 58". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (24 November 1971). "Screen: Ravi Shankar; ' Raga,' a Documentary, at Carnegie Cinema". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ Ravi Shankar interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- ^ a b c d e "Past Winners Search". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ a b O'Mahony, John (8 June 2008). "Ravi Shankar bids Europe adieu". The Taipei Times (UK). Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Ghosh 1983, p. 56

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 66

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 221

- ^ a b c d e Neuhoff 2006, pp. 672–673

- ^ "Ravi Shankar, legendary sitar player whose music inspired The Beatles dies aged 92" at dailymail.co.uk/

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 195

- ^ a b c Lavezzoli 2006, p. 196

- ^ Rogers, Adam (8 August 1994). "Where Are They Now?".Newsweek. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 222

- ^ a b Piccoli, Sean (19 April 2005). "Ravi Shankar remains true to his Eastern musical ethos". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "'Rajya Sabha Members'/Biographical Sketches 1952 – 2003" (PDF). Rajya Sabha. 6 January 2004. Retrieved 29 July2010.

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 197

- ^ "Shankar advances her music". The Washington Times. 16 November 1999. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ "LEGENDARY VIRTUOSO SITARIST RAVI SHANKAR ACCEPTS REGENTS' PROFESSOR APPOINTMENT AT UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO". UCSDnews. 18 September 1997.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 411

- ^ Idato, Michael (9 April 2004). "Concert for George". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Anoushka enthralls at New York show". The Hindu (India). 4 February 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Barnett, Laura (6 June 2011). "Portrait of the artist: Ravi Shankar, musician". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ London Philharmonic Site

- ^ Ravi Shankar Foundation Website

- ^ Menon 1995, p. 220

- ^ "SNA: List of Akademi Awardees – Instrumental – Sitar".Sangeet Natak Akademi. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ "SNA: List of Akademi Fellows". Sangeet Natak Akademi. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ "राष्ट्रीय कालिदास सम्मान" [Rashtriya Kalidas Samman] (in Hindi). Department of Public Relations of Madhya Pradesh. 2006. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ "Padma Awards". Ministry of Communications and Information Technology. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ "Citation for Ravi Shankar". Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Massey, Reginald (12 December 2012). "Ravi Shankar obituary: Indian virtuoso who took the sitar to the world". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Sir Ravi". Billboard (Nielsen Business Media, Inc.) 113 (19): 14. 12 May 2001. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ "Citation for Doctor of Laws honoris causa – Mr Ravi Shankar". Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ "Archive > Annual Archives > 1957 > Prize Winners". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Ravi Shankar – The 2nd Fukuoka Asian Culture Prizes 1991". Asian Month. 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ van Gelder, Lawrence (14 May 1998). "Footlights". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ PTI (6 December 2012). "Arts / Music : Ravi Shankar to be honoured with lifetime Grammy". The Hindu. Retrieved13 December 2012.

- ^ "Pt Ravi Shankar gets posthumous Grammy nomination". India Today. 7 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ PTI (6 March 2013). "Arts / Music : Ravi Shankar to be honoured with Tagore Award". Zee News. Retrieved 6 March2013.

- ^ Watrous, Peter (16 June 1998). "Pop Review; Just Music, No Oedipal Problems". The New York Times. Retrieved26 September 2010.

- ^ a b c "Hard to say no to free love: Ravi Shankar". Press Trust of India. Rediff.com. 13 May 2003. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Balaji temple in Hyderabad was stage for Pandit Ravi Shankar's secret wedding". The Times of India. Retrieved13 December 2012.

- ^ a b Lindgren, Kristina (21 September 1992). "Shubho Shankar Dies After Long Illness at 50". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved31 August 2009.

- ^ a b Venugopal, Bijoy (24 February 2003). "Norah's night at the Grammys". Rediff.com. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ Jamkhandikar, Shilpa (6 December 2012). "It's Ravi Shankar versus daughter Anoushka at the Grammys". Reuters. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Melwani, Lavina (24 December 1999). "In Her Father's Footsteps". Rediff.com. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Signing up for the veg revolution". Screen. 8 December 2000. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ "Ravi Shankar, Sai Baba, and the Huge Diamond Ring".

- ^ Varga, George (10 April 2011). "At 91, Ravi Shankar seeks new musical vistas". signonsandiego.com. Retrieved 25 April2011.

- ^ Allan Kozinn (12 December 2012). "Ravi Shankar, Sitarist Who Introduced Indian Music to the West, Dies at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

Mr. Shankar died in San Diego, at a hospital near his home. He had been treated for upper-respiratory and heart ailments in the last year and underwent heart-valve replacement surgery last Thursday, his family said. ...

- ^ "Classical legends leave their mark". The Times of India. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

REFERENCES[EDIT]

- "Shankar, Ravi". Brockhaus Enzyklopädie (in German) 20 (19th ed.). Mannheim: F. A. Brockhaus GmbH. 1993. ISBN 3-7653-1120-0.

- Ghosh, Dibyendu (December 1983). "A Humble Homage to the Superb". In Ghosh, Dibyendu. The Great Shankars. Kolkata: Agee Prakashani. p. 7. OCLC 15483971.

- Ghosh, Dibyendu (December 1983). "Ravishankar". In Ghosh, Dibyendu. The Great Shankars. Kolkata: Agee Prakashani. p. 55. OCLC 15483971.

- Lavezzoli, Peter (2006). The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1815-5.

- Massey, Reginald (1996). The Music of India. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-332-9.

- Menon, Narayana (1995) [1980]. "Shankar, Ravi". In Sadie, Stanley. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 17 (1st ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

- Neuhoff, Hans (2006). "Shankar, Ravi". In Finscher, Ludwig. Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik (in German) 15 (2nd ed.). Bärenreiter. ISBN 3-7618-1122-5.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1980). The Boys from Liverpool: John, Paul, George, Ringo. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0-416-30661-6.

- Sharma, Vishwamitra (2007). Famous Indians of the 20th Century. Pustak Mahal. ISBN 81-223-0829-5.

- Slawek, Stephen (2001). "Shankar, Ravi". In Sadie, Stanley. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 23 (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

EXTERNAL LINKS[EDIT]

| Media from Commons | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

- "Ravi Shankar". Official website.

- "East Meets West Music". Ravi Shankar Foundation.

- Ravi Shankar at AllMusic

- Ravi Shankar at the Internet Movie Database

| ||

|

Categories:

- 1920 births

- 2012 deaths

- Apple Records artists

- Artists from Varanasi

- Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur

- Composers awarded knighthoods

- Dark Horse Records artists

- Grammy Award-winning artists

- Hindi film score composers

- Hindustani instrumentalists

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Indian composers

- Indian film score composers

- Indian Hindus

- Private Music artists

- Maihar gharana

- Musicians awarded knighthoods

- Nominated members of the Rajya Sabha

- People of Bengali descent

- Pupils of Ali Akbar Khan

- Ramon Magsaysay Award winners

- Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale

- Recipients of the Bharat Ratna

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan

- Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan

- Recipients of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award

- Recipients of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship

- Sitar players

- All India Radio people

- Fukuoka Asian Culture Prize winners

- Indian composers of Western classical music

No comments:

Post a Comment